When it comes to intellectual property, the question of integrity more often comes up around the ownership of the work than on the quality of the property itself. Yet in my work on scholarly communication, I have made the case to consider how the concept of intellectual property arose, long before such an idea existed in law, out of an intense consideration of a work’s intellectual qualities or properties. It was through a long history of scholarly inquiry into such properties, dating back in the West to medieval monasticism, that we have come to take for granted that a text constitutes a distinct intellectual property. Scholarly publishing in some ways instantiates the intellectual integrity of the work through a process of editorial oversight and expert (peer) review.

This association of intellectual property and intellectual integrity begins to take on a far more modern sensibility, as this new publishing medium of the internet brings us both an Age of Misinformation, and an Age of Public Research Access. In this clash of the ages, how research access might serve to counter misinformation is considered, for example, by Briony Swire-Thompson and David Lazer in “Public Health and Online Misinformation: Challenges and Recommendations.” They remind researchers that they can “have an impact [on health misinformation] by publishing in open access journals, being more involved on social media platforms to communicate with the public, and directly contributing to information online [through wikipedia].” Yet Swire-Thompson and David Lazer temper their call by noting how, even when the public is motivated to seek out research, “the assessment of source reputability and the veracity of information is an extremely difficult task.”

So while the proportion of publicly available research increases each year, this access is only part of the story, a necessary but insufficient step, in redressing the rising tide of misinformation. Thus I have begun, as an educator and a researcher, to look for ways to better equip the public to assess at some basic level the intellectual integrity of the research they may be turning to take advantage of this alternative to the rising tide of misinformation. But before introducing the steps I’m taking to address this, let me acknowledge I’m not alone in these concerns.

In a parallel move, STM, the leading trade organization for science, technology, and medicine publishers, has launched a STM Integrity Hub this year. It is “a direct response to safeguard the integrity of science,” largely focused on the scientific integrity of the articles submitted for publication. STM will be providing its publisher-members with tools for screening deceptive studies, by detecting, for example, the use of duplicated images, and for ensuring that authors provide research data for others to scrutinize.

While STM seeks to ensure the integrity of the research, our work at the Public Knowledge Project is focused on helping the public assess “the source reputability,” as Swire-Thompson and David Lazer put it, which is to say the reliability of the publication. This follows from our development of open source (free) publishing platforms that enable and encourage publishers to provide greater public access to research.

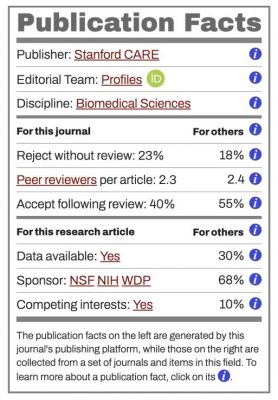

Our approach draws on the international convention of listing nutritional facts on food products to guide the public toward healthier diets. In particular, we have created a Publication Facts label that contains the essential ingredients when it comes to meeting scholarly publishing standards for journals and articles. Hoping to strike a familiar chord with the public, we have borrowed the design of the Nutrition Facts label in Canada and the United States.

The label gathers in one place what’s pertinent for assessing the research basics, while highlighting what sets research apart from other sources. For each article, the label offers a record of editorial oversight and peer review, as well as pointing out if the data is available to others, who the funders are, and if there are competing interests. Instead of looking through the website to learn about, for example, the journal’s editors, you can click on editorial team “profiles,” which takes you to their names, affiliations, and, through another link, their (ORCID) profiles. The same can be done with the journal’s peer reviewers from the previous two years, just as one can compare the journal’s peer review process to that of other journals in this field. Each line has an information link for learning more about how this information relates to publication integrity.

We have only begun to test the Publication Facts label with the public, starting with a few classes of high school students, to be followed by medical students, journalists, and social media users. The high school students had little trouble using the label to assess points of trust and caution in considering a study: “It was so easy and nice; I like the format; I’m already familiar with it.” They also offered advice to further improve the design and wording. So the label you see is in the process of being further improved as a tool for the public to assess research basics.

While we’re still at an early stage in this Journal Integrity initiative, it seems important to inspire and encourage others in scholarly publishing to consider how they can help the public in this Age of Misinformation find some hope in the growing public availability of research. To state the obvious, much depends on it.

The post Intellectual Property Integrity and Public Access to Research appeared first on Slaw.